Today we are open-sourcing our ODBC adapter for ActiveRecord, which allows Ruby on Rails applications to communicate with ODBC-compliant databases. The impetus for this work was an effort to update one of our APIs to run with the latest Rails and ruby. Along the way we released Rails 3.2.x, 4.2.x, and 5.0.x versions of the adapter, along with deploying incremental upgrades to our API as we went. Below is the story of how we made it happen.

ODBC

ODBC (or Open Database Connectivity) is the specification of an API that acts as a common gateway through which a client program can access disparate databases without having to account for individual interfaces. In the Rails world, this is largely analogous to ActiveRecord, which acts as an ORM wrapper around databases and allows applications to communicate with them with the same API.

ODBC itself has been around since the early ‘90s. In 2001, by virtue of ruby’s ability to be extended by C libraries, Christian Werner wrote a ruby wrapper for the ODBC C library. Then in 2006 Carl Blakely wrote an ActiveRecord ODBC adapter for Rails 2.1. Both of these libraries work with most of the commonly used DMBSs that you would normally connect to using ODBC, including MySQL, Oracle, DB2, Progress, etc. Our API has used it to connect to both a Vertica database (in production) and a PostgreSQL database (in test).

Where we were

When we started this work we were running Rails 3.2.22.5 (the latest released version of the 3.x branch) and ruby 2.1.5. Our database connection was running through a minimally-touched fork of Christian Werner’s ActiveRecord adapter (it had been updated just enough to get it working in Rails 3). The fork also contained our own hacks to get it to function appropriately when connecting to our data warehouse (our in-house Vertica cluster).

Side-note: a large reason why it continued to function is that while the semantics of the functions implemented in the ActiveRecord adapters changed, the call signatures didn’t. In most cases they continued to take the same number of arguments - the values simply changed class. The values continued to respond to the same API, so the functions continued to work. This can likely be counted both for and against ruby depending on your proclivity for dynamically-typed languages.

Creating the adapter

It became clear that the biggest blocker preventing us from upgrading our API’s Rails version was the adapter. Through ActiveRecord’s evolution, it became progressively more difficult to minimally update our fork. We decided to take a ground-up approach and write our own ActiveRecord ODBC adapter that could be swapped in for our existing one. Using a combination of our existing adapter and Rails’ own MySQL and PostgreSQL adapters on the 3.2 branch, we ended up with our initial version.

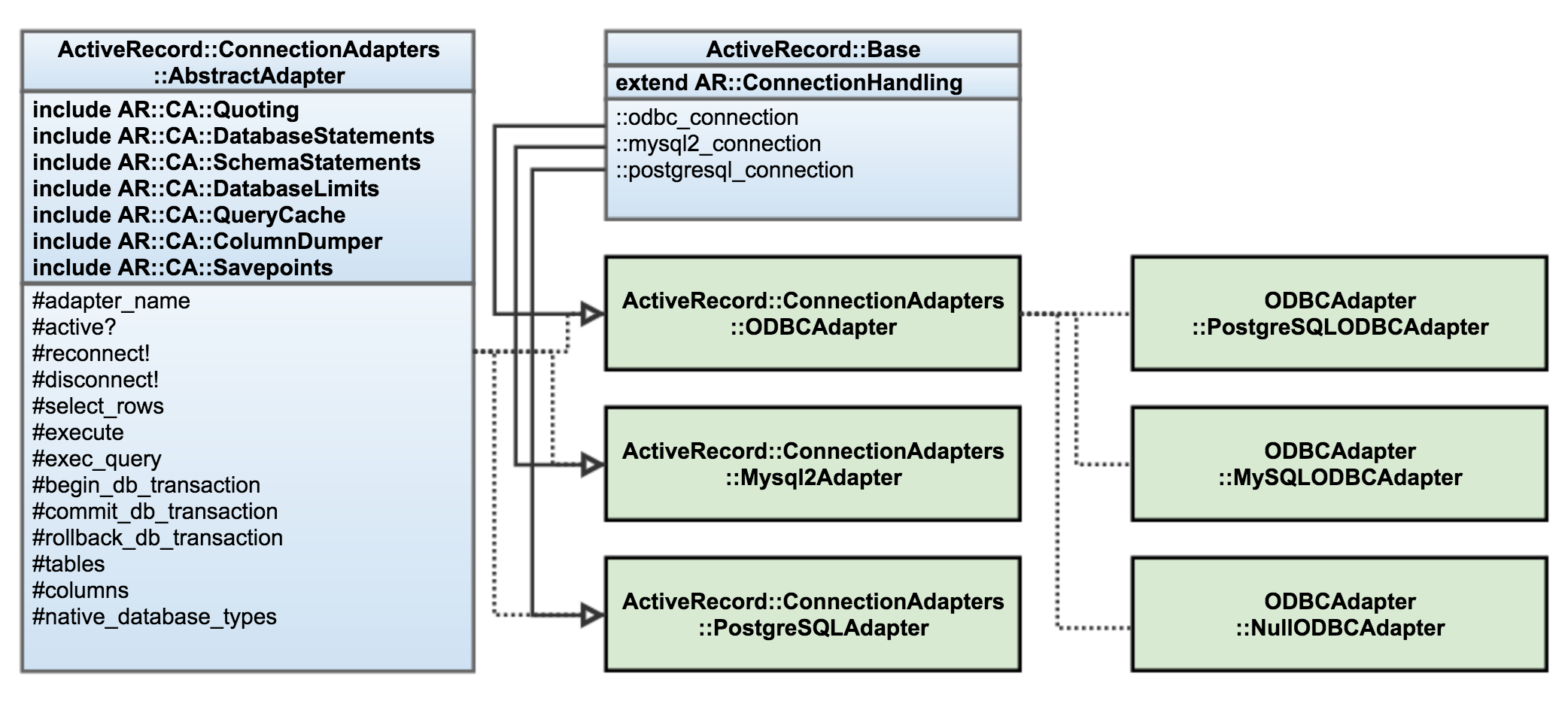

First, a few notes about the way ActiveRecord organizes its code. When a Rails application boots up, it establishes all of the necessary connections to various databases (in the default use case, just the one) through the ActiveRecord::Base::establish_connection method. This method calls out to ActiveRecord::Base::*_connection, where the * is whatever value you specify for the adapter key inside your database.yml. This function is responsible for creating a new adapter object (a subclass of ActiveRecord::ConnectionAdapters::AbstractAdapter), which is then returned and used as the active connection. The subclasses implement the behavior necessary for the individual DBMS to fulfill the correct interface.

Implementing the shared behavior

While some functions needed to be implemented differently for each DBMS (mostly schema-related logic), some could be shared because of ODBC’s abstraction. The functions that needed to be overridden in order for us to get feature parity with our existing adapter were:

- the

#adapter_namefunction - the connection management functions:

#active?,#reconnect!, and#disconnect! - the execution functions:

#select_rows,#execute, and#exec_query - the transaction management functions:

#begin_db_transaction,#commit_db_transaction, and#rollback_db_transaction - the schema functions:

#tablesand#columns - and finally, the

#native_database_typesfunction

In test mode we were using PostgreSQL as a suitable proxy because of the ability to quickly create and seed a new database in both CI and a developer’s laptop, so our first priority was getting a passing test suite for that DBMS. Fortunately, at this point we were able to lean heavily on our existing codebase to function as a test suite proxy. Running our API’s tests allowed us to iterate quickly and remove bugs as we found them.

Supporting multiple backends

In order to support multiple backend DBMSs, we defined a subclass of ODBCAdapter for each one, overriding the necessary behavior. When a connection is first requested, the ::odbc_connection function queries the connected DBMS for the name and then instantiates the associated ODBCAdapter subclass. If none is found, it creates a null connection. Below is a diagram describing this hierarchy:

The null connection actually works in most cases for non schema-related queries for databases that mostly reflect the SQL standard. ARel does a pretty good job of assuming the correct quoting and everything tends to work out. This means that for our own purposes, we didn’t need to create a full-blown Vertica adapter, we only needed to override the methods that we were using.

We built out the ODBCAdapter::register method to allow the end user to create their own adapters specifically for this purpose. A minimal Vertica adapter is effectively then:

Upgrade, swap in, test, repeat

Once we had the adapter built, we swapped it in for our existing adapter. We then began the painstaking process of upgrading both Rails and ruby versions. Along the way we encountered the various improvements that had happened to ActiveRecord over the years, including the type map in Rails 4.2 and the introduction of SqlTypeMetadata in Rails 5. Upgrading to ruby 2.4 proved somewhat difficult because of rb_scan_args explicitly checking the number of arguments provided (which became the difference between ruby-odbc versions 0.99997 and 0.99998). Eventually we ended up with our API running Rails 5.0.2 and ruby 2.4.0 in production, using the latest version of our adapter (just in time for the 5.1.0 beta to be released the following day).

Polymorphism and lessons learned

Polymorphism is a common pattern in programming. You define a common API that multiple objects implement, allowing them to be treated as the same type in various contexts. The name may vary by language: it’s referred to as interfaces (Java, PHP, Go), traits (Scala, Rust), and even roles (Perl). In ruby, it doesn’t have a name; the enforcement of the API’s contract is left to the programmer. Advocates of statically-typed languages mark this as fault for ruby: you can’t rely on the compiler to indicate that a method that needs to implemented hasn’t been.

On the other hand, in ruby there is no need to explicitly indicate that multiple objects respond to the same methods. This opens the door for some of the biggest flexibility in ruby, e.g. using method_missing to build mocks in tests, adding a try method to both Object and NilClass, or implementing to_json in various classes so that they can be serialized properly.

Both sides of the argument were displayed while building this adapter. Finding the correct methods to implement was a matter of relying on documentation and source code, not relying on a compiler. However, we were able to quickly switch in the adapter and test whenever we made incremental improvements. The lesson this highlights more than anything else is that modern programming languages make tradeoffs in design - as programmers it’s our job to take advantage of the strengths and cope with the tradeoffs. This as opposed to bemoaning the weaknesses and citing them as a reason the language is dead or dying.

Either way, we are now successfully connecting to our data warehouse using ODBC, running Rails 5.0.2 and ruby 2.4.0. The adapter is up for public use on rubygems.org, feel free to use it yourself to develop your own Rails applications. When you do please share your experience, approach, and any feedback in a gist, on a blog, or in the comments.